Who cares about the Establishment these days, anyway?

Thoughts about the relevance of the canon and who creates it

In February, I was invited to speak about alternative canon formations – specifically in spoken word and music, and for minority (BAME) writers in the UK as part of the Sorbonne University’s Canon Factory series of events. (For those of you who are not aware, one part of my life and career has been academic research, and a lot of the writers, poetry and ideas that I work on crossover into the kinds of creative work I try to share on here.)

This is part of a new series of essays, that I will be publishing between my usual plant-and-apocalypse poetry.

I realised that I had always been thinking about the canon, about canons, about “the establishment” and what’s outside of it, for a lot of my life. I hadn’t necessarily been thinking about it in terms of canonisation, however. What it comes down to is cultural power – who decides what (or who) is considered central to a culture, to a nation, which in the case of literature, means, which writers and which texts. Who does hold this power? What does ‘the establishment’ mean today?

The Establishment is present in almost all the theoretical and critical works piled up by desk, implicitly or explicitly.

As often, there are longer and shorter answers to these questions. In many ways, literary production, and perhaps most particularly in poetry, is proliferating ever-more outside of what we might call ‘the establishment’ today, at least in the British context (though the same seems to be increasingly true elsewhere, as both my research and that of other speakers at Canon Factory events seems to show [link in French]). However, it’s relatively easy to know what sort of diversity is being published (or broadcast, or written…) at the time when it is happening, if you look in the right places. The internet has of course made this exponentially easier. By this logic, there almost certainly has always been a large production of poetry, and other forms of literary writing, beyond the establishment, however it has not always been canonised. As such, whether temporarily or permanently, it has in many ways been ‘lost to history’, and whatever role these many works may have played in the construction of our cultures, societies, ideas of communities, nations, and selves, has been forgotten, or at least somewhat sidelined.

So, what then is ‘Canonisation’?

This is perhaps a more complicated question than it might appear. Essentially, it is the process by which certain works become considered a part of the canon, and as such considered as classics, central to a literary tradition, and by extension, to a culture. When we think about works like the plays of Shakespeare or the novels of Austen or Dickens, they are clearly canonical. Although Austen fell out of favour for a couple of decades immediately after her death, all three of these writers have remained canonical for extended periods – their success spans centuries. Other works have been considered classics for certain periods before dropping off lists of what makes up the ‘canon’; still others were not particularly successful or well-seen at the time, but are now considered classics (for example, Moby-Dick, or the poems of Emily Dickinson). What this should make clear is that there is nothing fixed about the canon, and that canonisation is an ongoing process: a work needs to not only gain but maintain a certain status to be considered canonical, or a ‘classic’. (Lincoln Michel has written about this on this very platform.)

Canonisation: Overlapping Processes Overseen by Fallible Humans

To start at the beginning, and at risk of stating the obvious, a work needs to be published. We cannot know how many works (of all shades and qualities) could have become classics, had they been published: had the writer had the right connections, had it been to an editor’s tastes, or even had it been written down at all, in the first place. Once a work is out there in the world in a format that can be accessed and consumed (note that I am avoiding limiting this to the idea of a ‘book’), it then faces the challenge of being accepted (at least) and promoted (directly or indirectly) by what we might call ‘the Establishment’. ‘The Establishment’ is one of those words that everyone sort-of-knows what it means, and so we throw it around a lot (to the extent that we even use the English word in French, so it must Mean Something). The Establishment is made up of the institutions that wield cultural power: major publishing houses, major broadcasting channels (TV, radio, cinema, internet…), education and culture ministries, and the like. In reality, the people who make up the business end of the Establishment are what Anthony Anaxagorou and others refer to as “gatekeepers” in Sarah Crown’s comprehensive and optimistic Guardian article on the spoken word and instapoetry boom, ‘Generation Next’ (2019). These gatekeepers will have their own ideas of what constitutes literary quality, most likely largely informed by their own education and the tastes of the circles that they move in. Whilst there have been some evolutions (I shy away from the loaded term ‘improvements’, but I still want to put it out there), the consolidation of a work as a ‘classic’ does not happen overnight, and such individuals and tastes have by and large been drawn from the most privileged classes and rarefied cultural circles over the last couple of centuries. Of course, even these people’s tastes change – what was once too experimental, or too crude (i.e. a lot of early twentieth-century Modernist writing and its wake), is now canonised. You might not like Woolf or Joyce (though I do) but it would be hard to argue that at least some of their novels are now considered canonical works of English Literature (to avoid any confusion over Joyce, I’m referring to the canon of the language and not the English nation – though there is of course overlap between the two – Woolf and Joyce are widely read outside their native countries).

My own first notions of what classic works of literature were came from the kinds of conversations about ‘books’ that family and family friends around me had when I was growing up (and the frequency and way in which writers or works were mentioned) – I know now that to even be party to these conversations was a considerable cultural privilege.

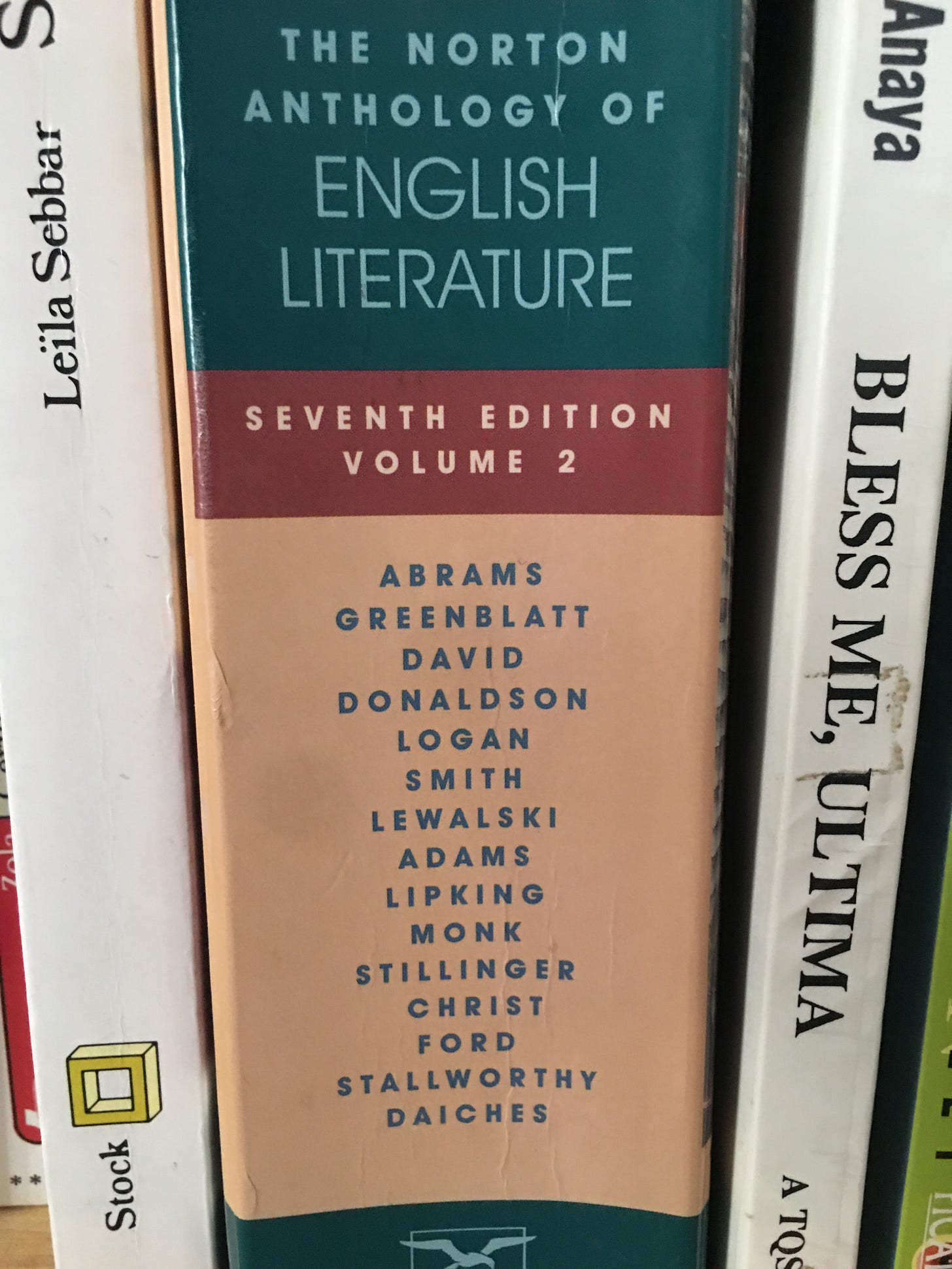

The Norton Anthology was the most concise (in terms of physical volume, but certainly not wordcount) representation of the canon for me as an undergraduate Literature student.

All of this may seem obvious to some of you, but I’m trying to lay the groundwork to talk about the kinds of ongoing canonisation, the contemporary, twenty-first century processes that are influencing what works are now classic, well-studied, widely-read, or at least well-regarded (and these are not three versions of the same thing). What will the canons of the future be? Will there be a future canon?

This brings me back to my starting point, and to the talk I gave in February. Things are changing, things are proliferating. Of course, a large number of the writers whose works have been canonised are from the groups that had more power, more access to education, more access to publishing: the wealthy, the western, and more often than not men. These have also been the main demographics of the gatekeepers of establishment institutions. Not only, not uniquely, not everywhere. But I’m interested in how this has been changing, in the wake of decolonisation and mass migration, in the wake of broader and more critical approaches to thought, to culture, to society, to literature.

Over the next few weeks, I’m going to look at how changes in publication and its gatekeeping (and perhaps most particularly the internet), and in the boundaries between and definitions of genres and forms (i.e. what constitutes literature), changes to the British education system (and the roots of canonisation and the concept of English Literature in universal education), as well as broader changes in society are creating new forms of canon, pluralising what a canon might be, and thinking about whether this makes it more or less powerful or relevant today – and how this might play out in the future. A particular focus, coming out of my own research interests, is in postcolonial and BAME writing, and also in the place of the nonhuman (or what we often refer to as ‘nature’). In a country like the UK, and perhaps most particularly England, ‘nature’ (animal, vegetable, mineral, landscape) is everywhere in the literary canon. But is it ever represented with agency? Do nonhumans contribute to the canon, to the way a culture represents itself?

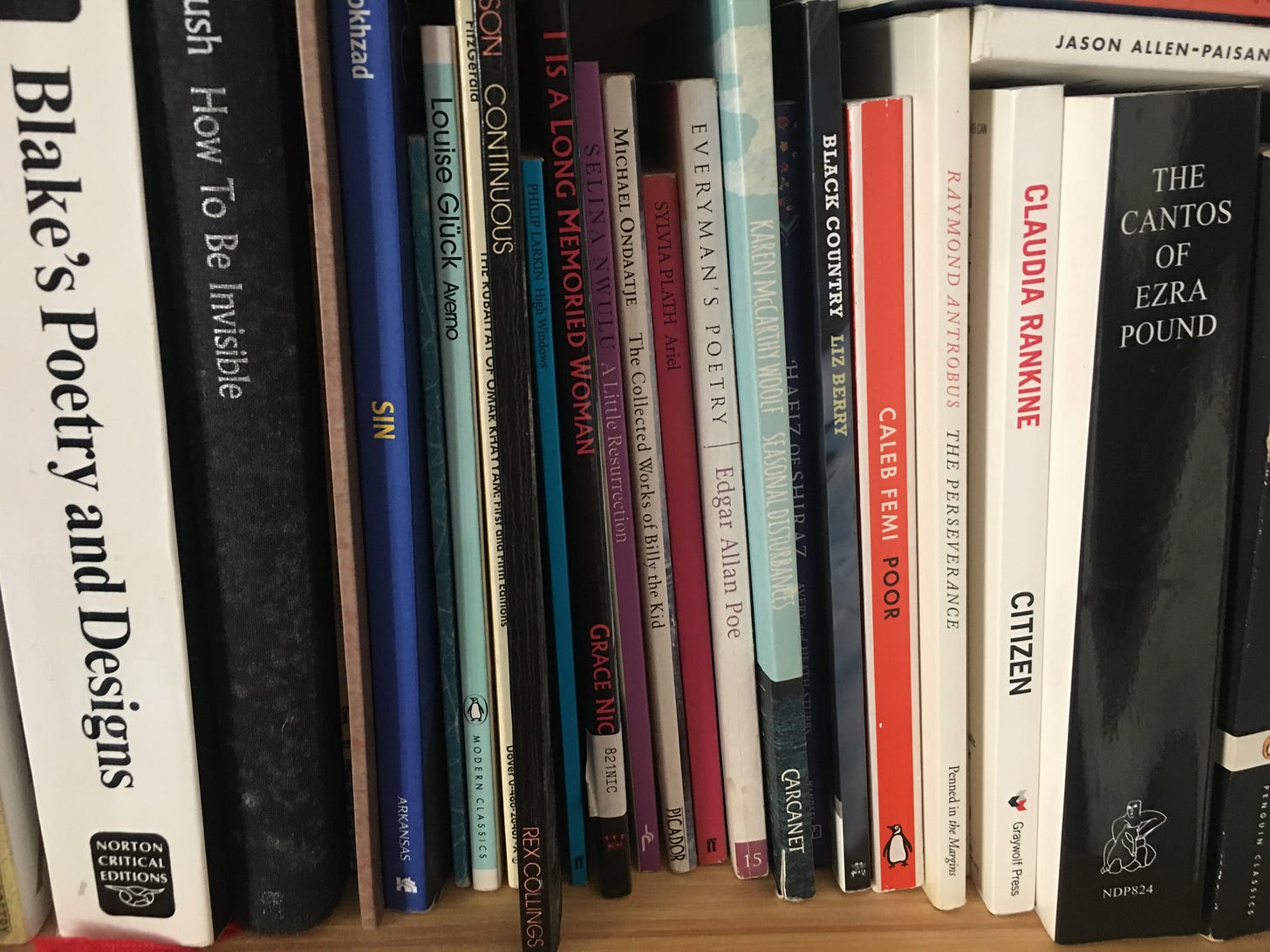

Poetic works in varying degrees of canonisation…

I hope you’ve enjoyed this introductory mini-essay and will enjoy following through some of these ideas with me. I’d love and appreciate hearing any comments, questions, opinions or feedback you may have here.

And once again, it’s the internet – so if you like my work, please do click on the like button, it helps me gain reach and lets my ideas spread further and interact with more people. If you have the means, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber – you’ll get access to more poetry, more in-depth essays, and contribute to the publishing of my first collection, receiving a physical copy when it comes out early next year.