Who Establishes the Establishment (Does Anyone)?

Inclusion and exclusion - mass education, canonical women writers

And who and what might be included within its invisible yet gilded perimeter fence?

Following on from the mini-essay I published a couple of weeks ago, I wanted to focus on who and what actually constitute the establishment and the canons of literature contained within, or produced by it, today, before looking – in my next canonical musing – at how this might change, or continue to change – and how. For clarity, I’m referring to the UK specifically here, though there are many parallels with other Western European nations during the industrial-colonial period, particularly France (In the US, for example, compulsory education was implemented on a state-by-state basis over a longer period).

Why am I writing about this now? Well, knowing the history – and construction – of culture and of what is presented to us how, by whom, seems more pertinent than ever (and it’s always pertinent). Literature is my passion but the hierarchies of power that exist within it, that created the canon as it is and has been, and that are perpetuated in part by it, are important to be aware of. That doesn’t mean you – or I – can’t appreciate works of canonical literature even if they may carry problematic messages or simply not represent numerous parts of the population (and that doesn’t just mean women, ethnic minorities or queer people but also by and large, lower socio-economic groups, i.e. poor people). At the end of the day, it’s important to know who decides we think, and consider if this makes us think again or think differently? How have our attitudes to equality, to human rights, to power been created? What about climate change? How do we see the rest of the natural world? A lot of this is shaped through the culture we receive, the books we read, and the likelihood of our exposure to any given work of art or literature is in large part down to ‘the Establishment’.

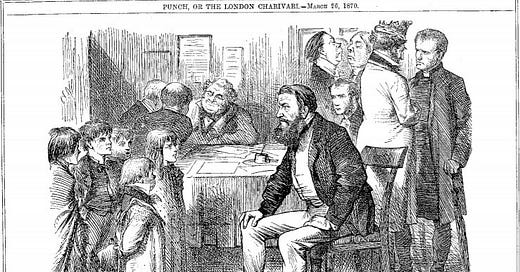

Punch caricature of Education Act of 1870

The 1870 Education Act started the process of making education compulsory for all British children, although in reality it took until the turn of the century for all children and young teenagers to receive free schooling. English Literature was central to education in – or perhaps, since – the nineteenth century. Matthew Arnold, also a celebrated poet, was a key architect of compulsory mass education in Britain, and saw culture, of which Literature was central, not only as a means of expression but as a way of enlightening and civilising the population. The treatment of the poor and working classes (then – as probably soon again – the majority of the British population) had many parallels with projects of ‘civilising’ colonised subjects through the imposition of British-European culture, purported as superior. In Culture and Anarchy, Arnold, arguing for the importance of education for all, described the uneducated as “Barbarians”, “Philistines” and a blind, unknowing “populace”. It was the latter that he held out hope for, he saw “culture as the great help out of our present difficulties; culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us.”[1] So the establishing of both education and the discipline of English Literature as a central part of it was anything but anodyne as a process. It should as such come as no surprise that the choice of what was taught or studied, and what was held up as central to the English literary tradition – i.e., what was canonised – was also, and has remained to a large extent, an ideological project whose criteria have been decided by a few people and applied to the many (that is, all of us who went through the British education system). I by no means wish to suggest that any or all of the works that have been taught or canonised as part of the English Literature tradition and its curricular declensions are not worthy of such a status (though please do suggest or debate any contenders in the comments!), but many other works and writers have been, and will inevitably continue to be, excluded. It is the criterion on which these processes of inclusion and exclusion work, their links to political power systems, and attempts to change them, that I wish to turn my (our?) attention to.

Before this, a clarification: English Literature as a discipline itself did indeed exist before mass education. Coming out of studies in rhetoric and their Germanic equivalent, philology, Literature was first (in the UK) studied as a discipline in Scotland, and only became a widespread University-level subject in the twentieth century. Its teaching in nineteenth century schools was part of general linguistic and cultural training. However the teaching of English Literature by whatever name played an important role in Britain’s imperial endeavours: the English book, as critic Homi K. Bhabha has famously pointed out, took on an almost mystical symbolic value in the process of colonisation, containing and representing western knowledge and ‘civilisation’.[2] The new colonial elites were educated to become ‘English’ (or indeed, French, in a very similar process in the French Empire) through the teaching of not only the language but the Literature.

Homi K. Bhabha. Photo credit jeanbaptisteparis @ Flickr https://www.flickr.com/people/49503077999@N01

A lot more has been said and written about this (including by me!) but in the interests of concision, it should thus not be too difficult to see the complicated, problematic relationship between the literary establishment and its canon, on the one hand, and on the other, working class people (and by extension, working class writers) and colonised people and their descendants, and BAME people more generally (and again, by extension, post-colonial and BAME writers). This is without touching on women writers and their works (some of whom it could be argued did have a canonical status by the end of the nineteenth century, but who nonetheless did not wield the same culture power) – much less (overtly) queer writing, a far more recent consideration.

We’ll get to nonhuman voices later, I promise.

In the rest of today’s piece, I’m going to explore how which works have been canonised, particularly by marginalised writers, starting with the place of women in the British literary establishment and canon.

In upcoming mini-essays, I will then be looking at how these processes of canonisation have and have not changed, and what cultural imaginary (of the UK, particularly) has been created and perpetuated by them. A part of this is the important place of nature in this cultural imaginary, of plants, animals, landscape: how do they contribute to the canon, are they ever represented as anything than passive objects?

I’ll also be looking into the question of solidarities and links between different marginalised groups/work and emerging canons, as well as considering one of my current research questions: is there a difference between how writers from historically dominant or oppressed/marginalised groups represent, or try to represent, nonhuman subjects and voices?

If my work interests you, please do interact - Substack is a great place to start a conversation. Just clicking on the like button also helps me gain more reach. If you have the means, please do consider supporting my work with a paid subscription or one-off donation.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Somewhere's Son to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.