Who Else Has the Establishment Been Keeping Out or In?

On the development of immigrant-origin and ethnic minority literature in the UK

In the last of my mini-series of mini-essays on the Literary Establishment, the English Literary canon and how these have created culture through processes of inclusion and exclusion, I looked at the history of the canon and the place of women writers within (and without) it. In this week’s piece, I’ll be looking at the place of ethnic minority writers in ‘English Literature’.

Next time I’ll be taking the slightly different angle of seeing how the nonhuman has both been central to a literary tradition and culture where ‘nature’ is everywhere and yet (for both obvious and less obvious reasons) rarely heard. The final essay in the series will look at new forms of canonisation, alternative canons, and how the place of previously marginalised subjects (both authors and not) has changed – and the current limits to this.

Photo © Contraband Collection/Alamy Images and Alford Gardner

To pick up where I left off, the period after World War II was the period of decolonisation of the British Empire, accompanied by the first ‘waves’ of mass immigration (often as invited workers) from colonised and former colonised territories[5]. During this period, Caribbean Voices on BBC radio (1943-1958) was already starting to broadcast poetry from what was then called the ‘West Indies’, and beyond. Whilst the colonial situation that underpinned this was of course problematic to say the least, this show opened the establishment door to writers that would not today be ticking the ‘White UK’ box on equal opportunities forms.

During the 1950s and ’60s, immigration continued apace, with the growth of notable South Asian, as well as Caribbean and African immigrant-descent populations, in the UK, particularly in major cities, ports, and areas where the demand for manufacturing jobs led to immigration being actively encouraged for many years: a stark contrast to the rhetoric and politics of recent decades. Over the following decades, populations of different sizes from beyond the former British Empire have also immigrated to the UK. An increasing backlash, was countered from 1965 on by three Race Relations Acts, which aimed to ban discrimination and promote inclusion. This was accompanied by an increasing number of measures aimed at restricting immigration, notably the end of automatic birthright citizenship for the children of non-naturalised immigrants in 1983 – a measure that could have had an impact on my own life.

Successive British governments’ approaches to integration of immigrant populations have largely been described with the term ‘multiculturalism’, as opposed to ‘assimilationist’ approaches in other countries such as France; notions of citizenship remain generally undefined, public expectations and ideas of what constitutes ‘Britishness’ and/or integration have varied massively from politician to politician and even from person to person. Despite the de facto possibility of an easy integration without cultural sacrifice, this is rarely if ever the case, and marginalisation and discrimination have remained major issues.

Nonetheless, in terms of culture, the influence of minority or marginalised culture could already be felt by the mid twentieth century in British music, influence by jazz, R&B, rock’n’roll and other forms with their origins in black American culture. It is difficult to overstate the importance of music to British popular culture: it is the third biggest market for music in the world, leading Germany (which has 18 million more inhabitants) in Europe and with over 50% more sales and listens than France, with its comparably-sized population. Equally, it should come as no surprise that overlapping with (and sometimes promoted as) music, the recording and performance of poetry have been central to its popularity and promotion in recent decades. The importance of popular culture was given academic attention from the early 1960s, with the foundation of Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham, and the leading figure Stuart Hall, himself originally from Jamaica and part of the Windrush generation, moving to the UK to study at Oxford. In 1964 he published The Popular Arts with Paddy Whannel – his work will later go on to focus more specifically on black and ethnic minority culture(s).

A smattering of literary works by immigrants and their descendants were published between the 1950s and 1970s, but it was really with the ’80s (notably with Hanif Kureishi) and ’90s that minority voices became a major force in British novel writing, culminating in what has been termed the ‘Millennial London Novel’ exemplified by works such as Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, Monica Ali’s Brick Lane or Gautam Malkani’s Londonstani. Various TV series and films from this period, often comedically or light-heartedly, also deal with the cultural clashes on confusions in newly multicultural Britain, and particularly its cities (from Kureishi’s My Beautiful Laundrette to The Real McCoy, Desmond’s, Goodness Gracious Me and later films like East is East and Bend it Like Beckham).

As such, it is worth noting that poetry and music were the first forms of widespread cultural recognition for BAME groups and individuals in the UK, notably with the dub poetry movement. To contextualise, the 1960s was a period of great popularity of poetry in the UK (which Corrine Fowler calls the “giddy heights of popularity” of spoken word[1]), notably with the Liverpool Poets and an increasing range of experimental poetry, as well as the popularity of less immediately challenging poets such as Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin. Indeed, debates over the nature and future of poetry and its speaking voice achieved unprecedented public attention at this period.

Photo: BBC

Amongst the most prominent poets of the 1970s and 80s was Jamaican-born Linton Kwesi Johnson (often referred to as LKJ), whose spoken word poetry, often set to the rhythms of reggae music, he called ‘dub poetry’, which later came to name a genre. Numerous poems (such ‘It Dread Inna Inglan’ or ‘Inglan is a Bitch’) deal explicitly with the situation and treatment of black people in the UK, and specifically England. Influenced by poets such as Louise Bennett, who helped consolidate Jamaican patois as a national language, Linton Kwesi Johnson’s creolised English and use of rhythm allowed him to gain success as a recording and performance artist, at a time when non-standard Englishes started to gain prominence in the poetic landscape, for example with the popularity of Tom Leonard’s Glaswegian dialect in Unrelated Incidents.

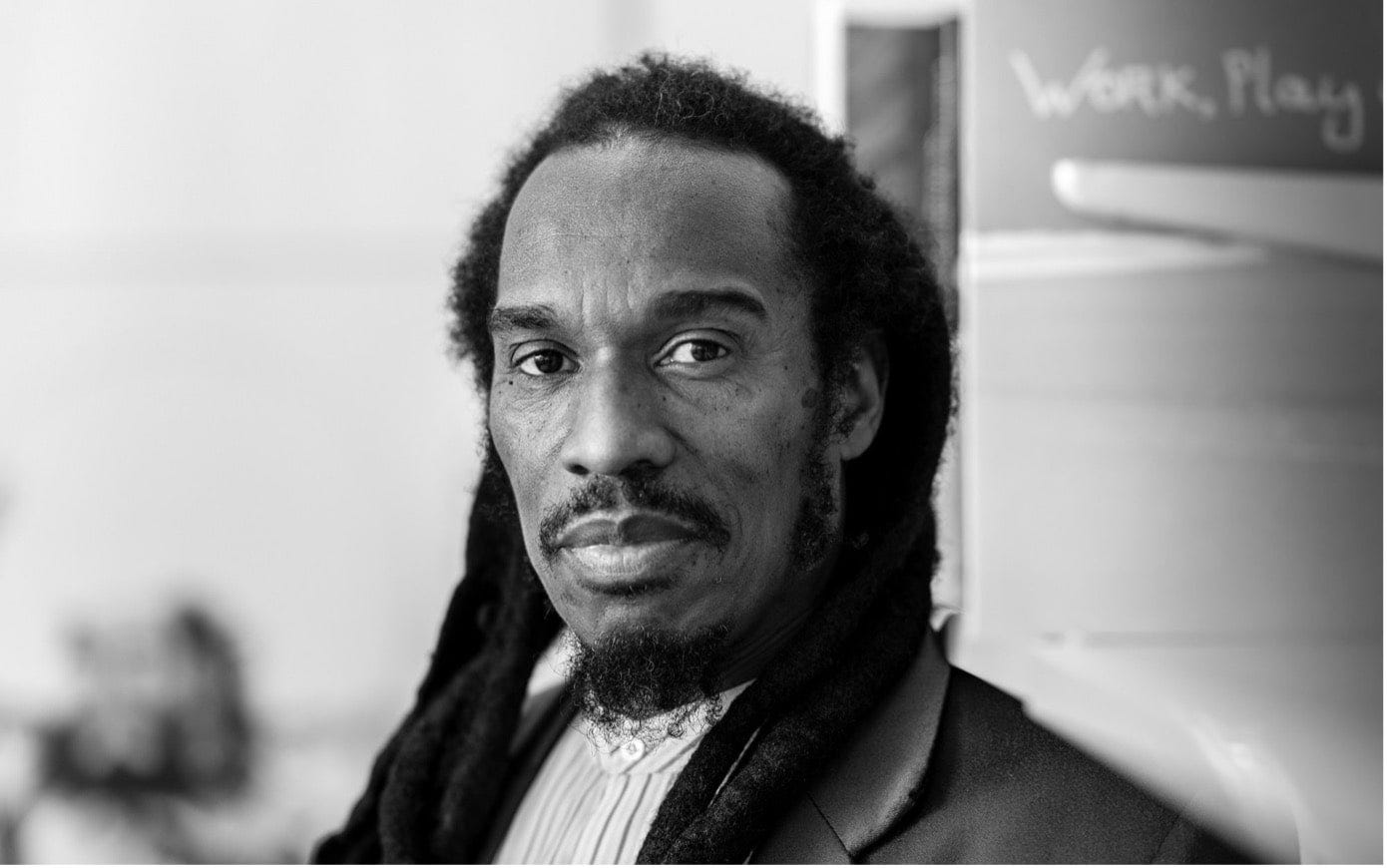

At the same period, Benjamin Zephaniah – born in Birmingham to Barbadian and Jamaican parents – started to achieve success with his spoken word poetry that can also be seen as part of the dub tradition, and frequently shows political engagement with the social realities, prejudices and discrimination of the time.

Photo: Lacuna / Richard Ecclestone

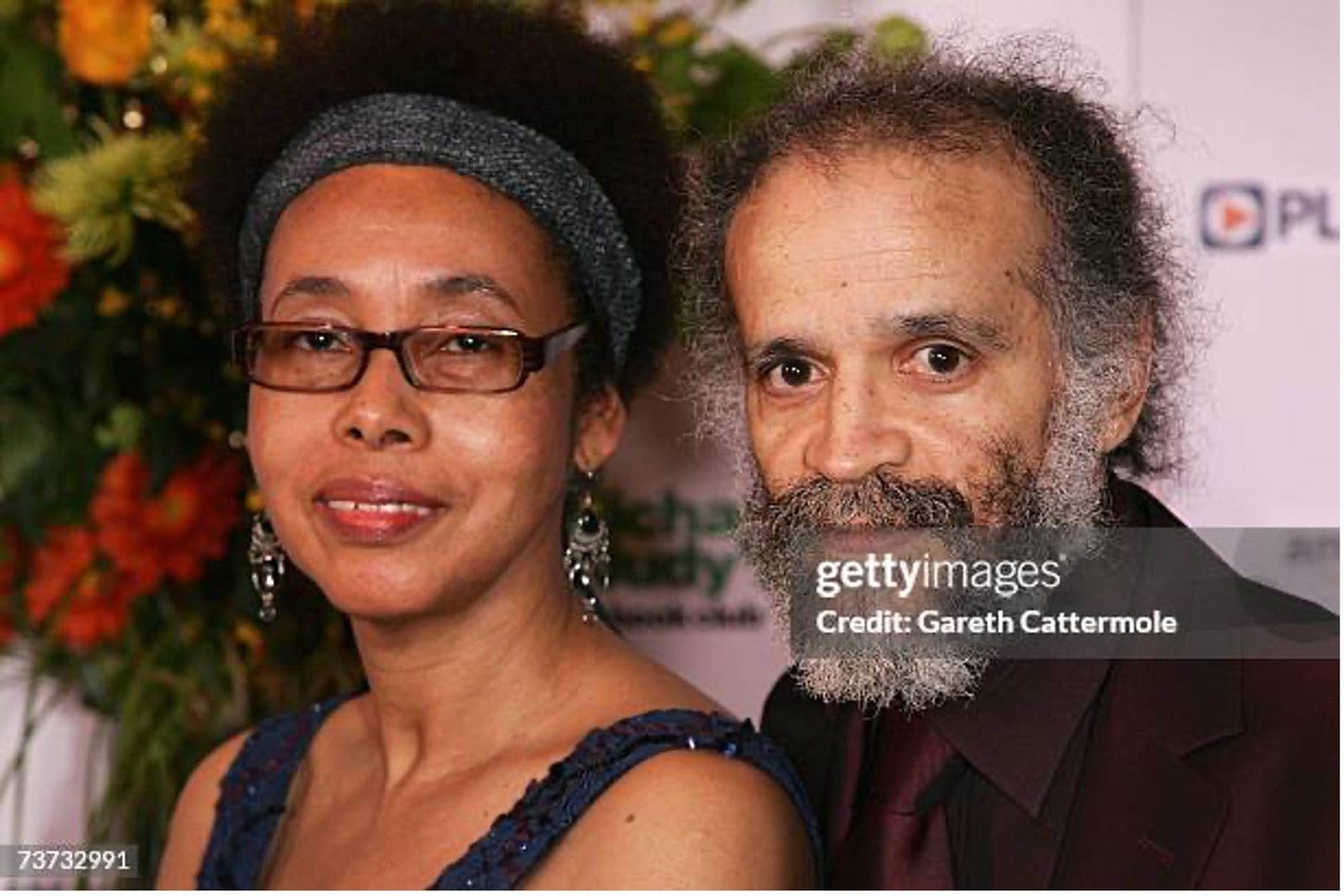

Two other major figures of what has become the British BAME poetic tradition are partners John Agard and Grace Nichols, who moved from their native Guyana (another Caribbean former colony) to the UK in 1977. Swiftly becoming prominent voices in the British poetry landscape, Agard is perhaps better known for his spoken word performances and Nichols for her public collections – although her voice performing poetry is warm and arresting. Nichols’ collection I is a Long Memoried Woman deals with the memory of colonialism, slavery and Caribbean heritage, and much of her other work deals with her experience and identity as a black Caribbean woman in the UK, including through linguistic creolisation. Various poems by Agard have become well known for their direct interaction with questions of cultural legitimacy, including ‘Half Caste’, ‘Checking Out Me History’ and ‘Listen Mr Oxford Don’, widely anthologised including on GCSE syllabi – a key element in what could be seen as processes of canonisation. Agard’s poems’ messages may rail against the establishment, but they are now disseminated by it, complicating the relationship between insider/outsider and protest/mainstream discourse. Might we see this as progress? In any case, this generation of Caribbean origin poets played an important role in consolidating minority poetry as a major part of the British cultural scene in the late twentieth century, and their work remains widely read and popular to this day.

So, to get to the key questions that I am asking, do poets of the level of popularity and recognition as Johnson, Zephaniah, Agard and Nichols now in some ways represent the literary establishment that once excluded, intentionally or not, minority works? Has the British Literary canon changed, and does this represent, reflect or even effect broader changes in culture and society?

My answer lands (or perhaps my answers land) somewhat painfully on the fence.

There is a fine line between the co-opting of specific poems or writers in the name of diversity and inclusion (whether well intentioned or not) and real, lasting change. Certainly, there are many ways in which we can see BAME writers as increasingly established within the literary and poetic traditions of Britain, beyond simply public popularity in terms of attendance or listening figures and book sales, which can be ephemeral and lost to history.

A first and obvious but worthwhile comment is that the very fact that these writers, whose initial success was now forty or fifty years ago, remain popular and widely read, points to something beyond a passing trend in taste. Institutional recognition, key to canonisation with anything approaching an Establishment Parthenon, has also been little short of prolific. (I don’t want to say that these four writers are the only BAME poets to have had such success, but am using them as examples, as they are at least amongst the most prominent by most measures.)

LKJ was rapidly honoured by cultural, literary and academic institutions, which at the time showed a certain openness to new, minority forms of culture and literature. Warwick University made him an associate fellow in 1985, and he became a professor at Middlesex twenty years later, pointing to his lasting importance and influence. Zephaniah was also lauded with many awards, and additionally played several television roles (including in the extremely successful series Peaky Blinders), giving a mainstream national visibility both to a minority face and voice. Both Johnson and Zephaniah released recordings of their dub poetry to national and international success.

Pointedly, however, Zephaniah refused the OBE (it’s of course worth noting what the aconym actually stands for, and its oft-noted significance for postcolonial British citizens); he then went on to refuse a Laureateship: “I have absolutely no interest in this job. I won't work for them. They oppress me, they upset me, and they are not worthy. I write to connect with people and have never felt the need to go via the church, the state, or the monarchy to reach my people. No money. Freedom or death.” (Zephaniah’s tweet on Poet Laureate consideration, 5/11/18) Of course, the previous laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, represented not only the first woman to take up the role, but also an avowedly feminist lesbian, bringing representation of until recently oppressed (or at least hidden) voices to the very fore of the national literary Establishment.

This of course begs the questions, can someone as avowedly anti-establishment as Zephaniah be considered canonised – even against his will? Does canonical status in terms of popularity, readership, and so forth, make someone a part of the Establishment? The example of Zephaniah suggests that in fact, they may be too – related, certainly – distinct things.

As a counter-example, Nichols’ I is a Long Memoried Woman also received the Commonwealth Poetry Prize in 1983 – certainly a prize in a (post-)colonial lineage but major recognition nonetheless. The Royal Society of Literature has also appointed an increasing number of BAME and other minority members, from Grace Nichols and Imtiaz Dharker and fellows like Zaffar Kunial right up to the President, Benardine Evaristo. It also has an important international (or perhaps transnational) role and presence, representing a significant opening up of the British literary Establishment.

If the Establishment is mainly institutional, is there just one canon? Our current era which is not only post-colonial and post-migratory, is one of globalised, transnational exchanges and influences, evident in the trans-Atlantic musical influences on post-WWII British music and indeed in the very form of dub poetry. Nowadays, such exchanges are vastly facilitated by the internet: social media in particular allows for an impression of proximity and intimacy as well as the rapid development and spreading of trends. In this context, it should perhaps come as no surprise that numerous women and BAME writers (often both) have achieved success as instapoets, broadcasting directly to their audiences and without having to pass through potential institutional and financial barriers (minorities still statistically being disproportionately poorer) or deal with publishing houses’ defensive claims that they already have a poet representing ‘the’ BAME voice.[2] Arguments about the literary quality of some such writers, though somewhat calmer than five years ago, still abound, but their success online has often translated to book sales and even a general increasing in sales of poetry in the UK. Such emerging writers and new traditions (potential future traditions?) offer new potential routes to success: whether this will lead to canonisation is another question.

However, a British BAME poetic tradition – something approaching a tradition – clearly does exist: a powerful way of considering canonical status is citation. Mixed-race rapper Loyle Carner’s 2022 single ‘Georgetown’, playing on his father’s and Agard’s Guyanese origins, interpolates Agard’s ‘Half-Caste’ and plays with its themes. As such, Agard’s pioneering presence in the British landscape has given foundations for future generations to build upon. In conversation with Zephaniah, Carner also pointed out the elder poet’s role in inspiring him, both as an ethnic minority and a dyslexic teenager and writer. Here we can see the creation of a lineage, echoing the ways in which famous Romantic poets and Victorian novelists remain much cited by subsequent generations up to the present day.

To end this week’s essay, I want to circle back to the GCSE anthology. For younger generations such as Carner, this is the touchstone for what the British – or even English language (it also includes not only Commonwealth but US American poets) – poetic tradition is. The ‘average person’, that is, everyone who goes through at least the English secondary education system, is not only taught but tested on a certain representation of the poetic canon. It is the Establishment reproducing a certain image of culture for future generations to see their country and its language and literature through. And it has changed significantly, as Julie Vanessa Blake’s extensive study has shown: of course, the number of poets remains, like the size of the anthology, limited, and only a few poets from recent generations have attained an ongoing established place on the syllabus (it is also worth noticing the corresponding removal of Rudyard Kipling for his representation of and association with Britain’s imperial past). In addition to now-established poets like those I have mentioned, ultra contemporary poets like Louisa Adjoa Parker, Raymond Antrobus and Caleb Femi have been included in recent years. Will they still feature in a generation’s time?

A lot of questions remain of course unanswered, including the intersections between different writers, influences and subject matters. One of these that I am particularly interested in, is the representation of the nonhuman. If it has been a long process for women and ethnic minorities (to say nothing of queer, trans or disabled writers) to gain a (sometimes uneasy) place within or close to the canon, then what can be said of the nonhuman subjects that make up our cultures, our ecosystems, our shared homes? Is it even possible for them to be heard? Do humans who have known oppression or subjugation or its heritages, show a particular sensitivity to or solidarity with oppressed nonhuman subjects (or indeed, with each other)? I will turn to these questions in the following parts of this essay series.

[1] In Fowler, Corrine. “The Poetics and Politics of Spoken Word Poetry”. The Cambridge Companion to British Black and Asian Literature (1945 – 2010). Ed. Osborne, Deordre. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2016, 177-92

[2] As a Guardian article, cited by Sara Greaves, points out, “The Free Verse report discovered that mainstream poetry presses – run overwhelmingly by white men – would routinely reject writers on the basis that they already had one poet to represent ‘the Asian voice,’ ‘the Black voice,’ etc.” (Peter Beech, ‘Britain needs a black poet laureate’, quoted by Sara Greaves in ‘Transcultural Hybridity and Modernist Legacies: Observations on Late Twentieth- and Early Twenty-First-Century British Poetry’ 164). This is reflected by Corrine Fowler who points out that “British Asian and British black poets are woefully underrepresented” on the publishing lists of the seven major publishing houses (Corrine Fowler, “The Poetics and Politics of Spoken Word Poetry” 182).